Posts by Juan Artola Miranda

The Wolf, the Fox, and the Ailing Lion (Aesopic Fable)

The Wolf, the Fox and the Ailing Lion is an old Aesopic fable first recorded by Émile Chambry in 1925 in France. It’s one of the classic stories about a cunning fox, and it has a clever twist and a grim ending. It’s one of my favourites.

As is tradition, this is a retelling in my own words.

The Fable

The lion lay in his cave. He was old and sick and soon to die, so the animals came to pay their final respects. All except for the fox.

The wolf noticed that his rival, the fox, was missing. “That arrogant fox shows you no respect,” he told the lion. “You have been a just king for all these years, and he cannot even be bothered to visit.”

The fox arrived just in time to hear the last of the wolf’s words.

The lion was furious when he noticed the fox there, skulking at the back of the cave. The fox came forward, begging for a chance to explain herself. “I am late because I have travelled all the way to the Spice Islands, where the cinnamon grows, seeking a cure for your condition.”

“And what did you find?” the lion asked.

“The wise doctors there know of just one cure, and you will not like it. You must find a wolf, consume his flesh, and wrap yourself in his warm furs.”

The Moral

The Wolf, the Fox, and the Ailing Lion has two moral lessons. First, someone who schemes behind another’s back often falls into his own trap. Second, it is better to give your master a solution than a problem.

If you liked this story, there are a few more dark fables about vicious kings. You might like The Monkey and the Lion’s Breath, The Frog King and the Snake, and The Two Horses.

The Monkey and the Lion’s Breath (Aesopic Fable)

The Monkey and the Lion’s Breath is an old fable often attributed to Aesop. It was first recorded somewhere in Western Europe in the 10th century. It’s credited to Romulus, which was a generic Latin name, not a specific person.

As is tradition, this is a retelling in my own words.

The Fable

When the lion made himself king of the jungle, he decided he would be a just ruler. He stopped feasting on the other beasts, limiting himself to the fruits and insects that they would eat. He made an exception for criminals, traitors, and dissenters. He would eat those. And for a time, that was enough to maintain his vigour.

Soon, though, there were too few animals to punish, and the lion grew hungry.

He took his subjects aside one by one, asking them if his vegetarian diet was making his breath smell. Some animals insolently answered that his breath did indeed smell, so the lion ate them. Other animals said his breath smelled fine, but they were lying, so the lion ate them, too.

Soon, it was the monkey’s turn. The monkey smelled the lion’s breath, recoiled in horror, and then proclaimed that the lion’s breath smelled of most noble cinnamon.

The lion couldn’t bring himself to eat an animal who paid him such nice compliments, but he was hungry, so he devised another scheme.

He called his doctors over and showed them how his stomach was growling miserably. The doctors were terrified. The lion explained that he must be sick. The doctors agreed. The lion suggested that perhaps monkey meat was the only cure. The doctors concurred. They killed the monkey and fed it to the lion, and the lion was satisfied once again.

The Moral

The moral of the Monkey and the Lion’s Breath is that the penalty for speaking up and remaining quiet is one and the same. There is no winning against a tyrant who wishes you dead.

If you like fables about tyranny, try The Donkey and the Onager, Aesop and the Runaway Slave, and The Two Horses.

My Ten Favourite Jewish Folktales

I was reading through A Treasury of Jewish Folklore. It was first published in 1948 and has since gone out of print. If you can get your hands on a copy, I highly recommend running away with it. For your health, of course.

The book has many, many different Jewish folktales, parables and legends. These are my ten favourites.

Read MoreThe Sheep, the Shepherd, and the Dog (Aesop’s Fables)

The Sheep, the Shepherd, and the Dog is a grim fable about solidarity. It can ostensibly be traced back to Aesop, if indeed he was ever more than just a character in a story. It was first recorded by the mysterious Babrius, probably in the first century CE. Little is known about him, but scholars believe he lived in Cilicia (now Turkey and Amenia).

This is a retelling in my own words.

The Fable

A long time ago, a long way away, there was a sheep that grew tired of spending her days under the watchful gaze of the shepherd and his dog.

“You shear my wool and weave it into carpets I never walk on. You take my milk and curdle it into cheese I never eat. Then you take my babies and do the same to them. Where is my share of the profit? You keep me here, eating dry grass from the mountain sides, while you and the dog feast on my labour!”

The shepherd thought himself a reasonable man. He set the sheep free, but she was eaten by a wolf before she could enjoy it.

The Moral

The moral of the Sheep, the Shepherd, and the Dog is that we are oft better together than apart. It’s a tale of solidarity. The sheep give their wool and cheese, the dog provides enforcement and protection, and the shepherd offers guidance and the rule of law. At the height of our arrogance and optimism, it can be easy to imagine ourselves better off alone, but that isn’t always so.

It also sounds quite a lot like what a racketeer might tell a restauranteur: “The world is a dangerous place, but I can protect you for just a small fee.”

If you liked this fable, you might like The Snake, the Farmer, and the Heron from Africa. Or perhaps The Mongoose and the Farmer’s Wife from India. If those fail, you could try The Lobster and the Sheep from here in Mexico.

The Man Who Looked for Cockroaches, a Mexican Parable

The Man Who Looked for Cockroaches is a modern Mexican folktale about a man who went looking for trouble. I want to call it a fable (because I prefer fables), but I suppose it’s a parable.

As is the tradition with folktales, this a telling in my own words.

The Fable

Not so long ago, a man moved into a beautiful house and was content there for many years. But one night, shortly after dark, right after he settled down for bed, perhaps because of some little noise he heard, a worry crept into his mind:

What if there are cockroaches beneath the floorboards?

The man pried up the floor to see what lay beneath, and lo he found them there, just as he had feared.

The man was never content in his house again.

The Moral

The moral of The Man Who Looked for Cockroaches is that if you go looking for things to be upset about, you will find them, and you will be upset.

My wife, whom I love very much, is especially bad at this. She looks up images of the mites that live on our faces, watches videos of flies laying eggs in food, and reads facts about how many insects we accidentally eat every year. The only results of her efforts are that she is less happy to have a face and eat food.

You’ve probably heard proverbs to the same effect: what you don’t know can’t hurt you, ignorance is bliss, and better to let sleeping dogs lie.

If you liked this Mexican folktale, you might like a few others. The Black Sheep is perhaps the most famous. There’s also the fable of The Lobster and the Sheep. Or, if you don’t like sheep, there’s The Rabbit and the Lion.

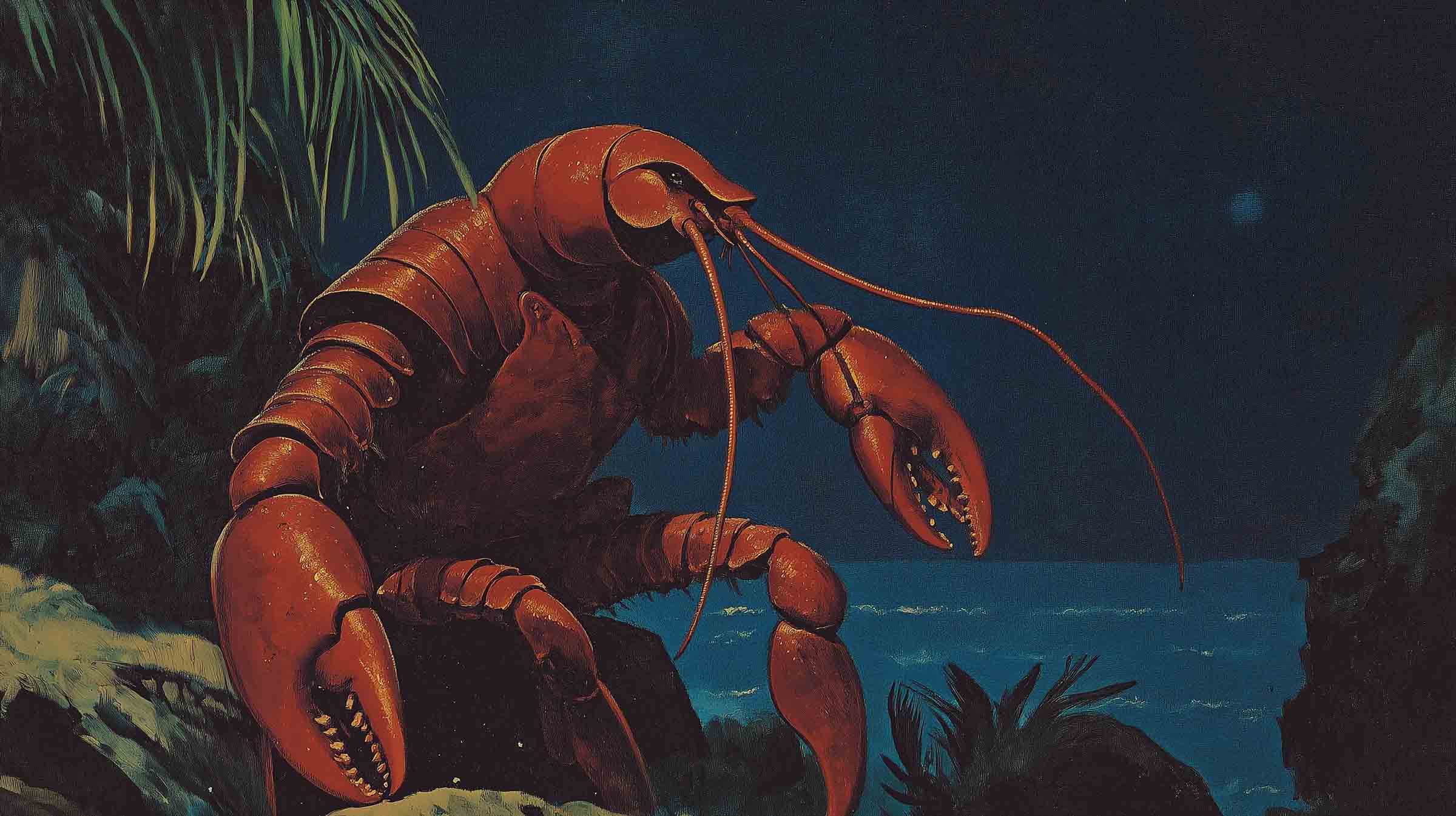

The Lobster and the Lamb, a Mexican Fable

The Monk and the Abbots, a Medieval Christian Folktale

The Monk and the Abbots is an old Christian parable first recorded by a 13th-century cleric named Odo of Cheriton. He wrote over a hundred fables and parables, usually Aesopic, and often with Christian sermons tacked onto the ends of them. This is one of my favourites.

In keeping with tradition, this is a retelling in my own words.

The Fable

The fable begins at a monastery long ago, with a generous abbot who gave his monks ample three-course dinners. The monks, though, had appetites that were not so easily quenched, and they grumbled about having too little to eat, saying, “Let us pray that he will die soon.”

Some time later, the abbot died, and a new abbot took over. He was a conservative man, so he gave his monks two-course meals. The monks complained yet again, saying, “Let us pray that he will die soon.”

Sometime in the future, the second abbot died, and a third took his place. This abbot was more austere with his rations, giving his monks paltry one-course meals. The monks were livid, and they prayed to God for the abbot’s quick demise. But one of the monks said, “Meanwhile, I shall pray that the abbot stays strong and safe.”

The others were aghast. “Why would you say such a thing?”

The monk explained, “Our first abbot gave us three meals, the second gave us two, and now we have one. If this trend continues, the next abbot will give us none, and we will starve.”

The Moral

The moral of The Monk and the Abbots is Seilde comed se betere, or, in more contemporary English, bad situations seldom get better.

Perhaps you’re hoping for the next politician to be better than the last, for a dastardly corporation to lose its monopoly, or for Google’s next core algorithm update to start sending more traffic to this website. But so far, the changes haven’t been good, and there’s no reason to think the next change will be any different.

I told this fable to a friend of mine, and he said that we ought to take matters into our own hands. If the abbot isn’t giving you enough food, perhaps it would be best to leave the monastery and strike out on your own, making your own good fortune. Perhaps that’s so. Or maybe I need to find some fables about the foibles of revolution.

Anyway, Odo wrote a medieval fable that’s quite good: Belling the Cat.

You might also like an old Russian fable: The Two Horses.

The Fable of Aesop and the Runaway Slave

Aesop and the Runaway Slave is one of the oldest Aesopic fables. It’s a controversial one, and you’ll soon see why: it’s a fable about slavery that seems to side with the master, not the slave. It has a valuable moral lesson, though, especially if you aren’t a slave.

The Fable

Aesop came upon a slave who was running away from his master. The slave recognized him and rushed over to recount his many misfortunes.

The slave told of how he had to serve his master elaborate feasts while his stomach gnawed at him. Of how he was forced to accompany his master on long journeys, sleeping in the cold ditch while his master found warm shelter inside. And of how whenever he tired, the master’s whip would renew his vigour.

“If I had done something to deserve this suffering,” the slave said, “I would bare it gladly. But I am innocent! So why must I live this life of hunger and agony? Why must I give the best years of my life to this cruel tyrant?”

Aesop knew well what it was to be a slave. He nodded along sympathetically.

The slave had many more hardships to agonize over, but he decided to cut to the heart of it: “I’ve decided to flee—to go wherever my feet will take me.”

Aesop shook his head. “If this is what you must endure for your innocence, imagine how miserable your life will be when you’re guilty of something!”

The Moral

The moral of Aesop and the Runaway Slave is that you shouldn’t add one problem to another. The same moral is repeated across a few of Aesop’s fables, often with even grimmer endings.

It might sound like a story a master would use to keep his slaves subservient, and it might be. But there’s some context to consider. Aesop was a slave who earned his freedom. Aesop may not have existed, but this fable was first recorded by Phaedrus, a former slave of Emperor Augustus during the first century CE. So, whether the fable belongs to Aesop or Phaedrus, it’s a story told from the perspective of a former slave.

If we set aside the issue of slavery, the moral is a wise one.

Many of us fall victim to a psychological fallacy known as the what-the-hell effect. It’s when something goes wrong, and you proclaim, “To hell with it, then!” and ruin everything.

For example, let’s say you’ve been faithfully following an oppressive diet, but one day, you break it by having an ice-cold glass of crisp Coca-Cola, shooting you over your calorie target. You tell yourself you’ve already blown your diet for the day, so you have a torta, then another, and then a third. When you wake up in the morning, you realize the diet is irreparably broken, so you continue eating junk food. And, of course, you get very fat.

This fable urges you to take another path. Let’s say you make that same initial mistake: you have the refreshing glass of Coca-Cola. But you refuse to add one problem to another. You don’t have the torta. You go back to following your miserably restrictive diet. And you continue losing weight.

For another example, my cuñado has a habit of hurling his video game controller whenever he loses a particularly tense game of Madden. Occasionally, the controller breaks. Once, it crashed into his television, shattering the screen. That didn’t make him feel any better about having lost his game of Madden.

When things go wrong, it’s wiser to make them better, not worse. Don’t cut off your nose to spite your face, jump out of the frying pan into the fire, or add insult to injury. Two wrongs don’t make a right, and neither do three or four.

Anyway, if you liked this fable, you might like some of Aesop’s other lesser-known fables, such as The Wolf and the Lamb, Two Wishes, or The Frogs and the Ox.

The Mongoose & the Farmer’s Wife (Indian Fable)

The Mongoose and the Farmer’s Wife is an old folktale from the Panchatantra, a collection of Indian fables from the 3rd century BCE. It’s a grim story about the danger, or perhaps value, of leaping to conclusions. I’ll explain the meaning at the end.

Read MoreThe Snake, the Farmer & the Heron (African Fable)

The Snake, the Farmer and the Heron is an old African folktale from the Hausa tribe, told throughout the northern regions of Nigeria and the southern areas of the Niger. It picked up even more popularity after being featured in 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene. It’s a story about how water doesn’t flow uphill. That’s a bit cryptic, I know. I’ll explain it at the end.

It’s one of my favourite fables. I’ve translated the fable into English and retold it in my own words.

Read More