Posts by Juan Artola Miranda

The Tragic Legend of Milo of Croton, the Man Who Carried the Bull

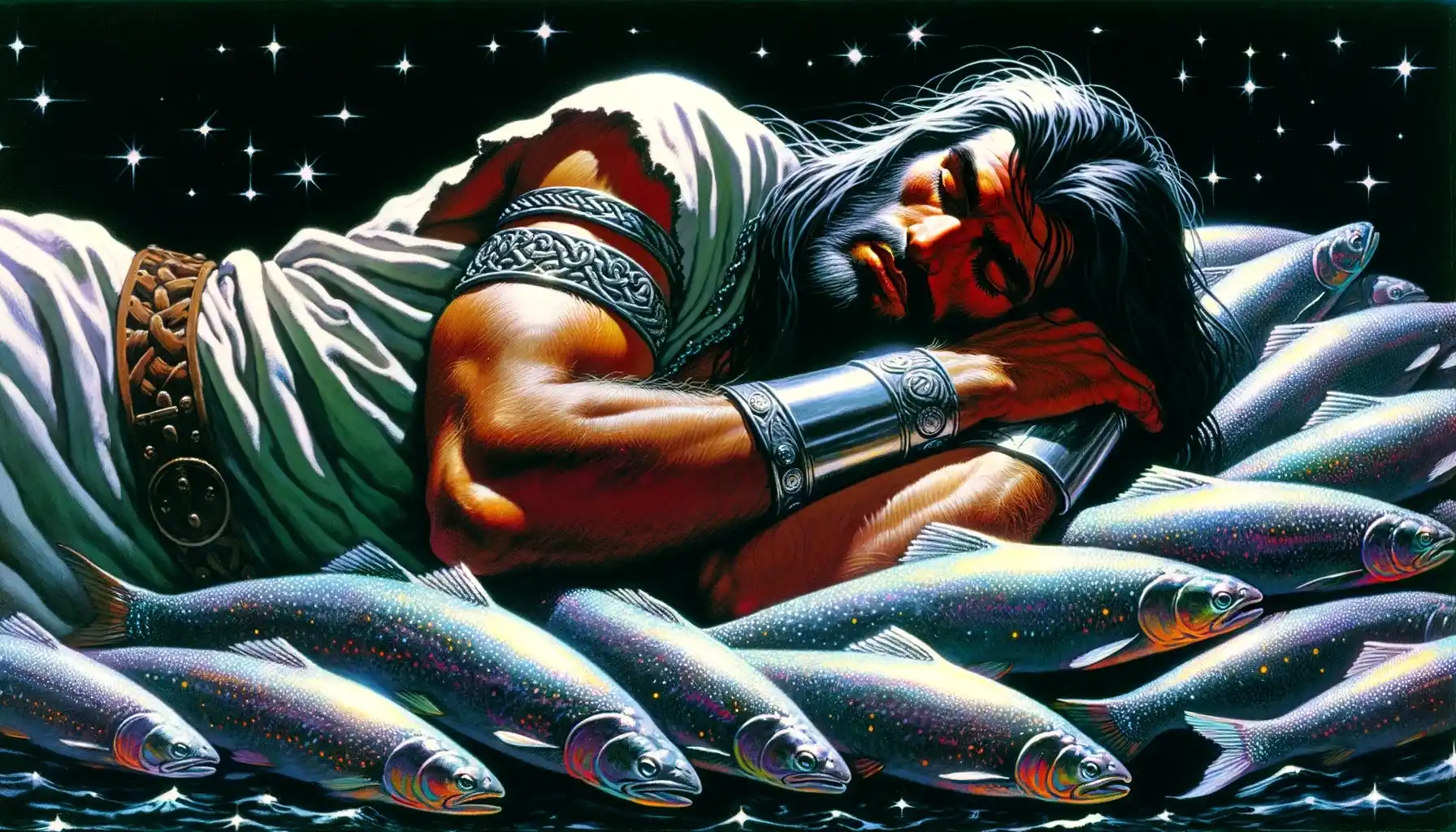

The legend of Milo of Croton is a tragic tale of gradual improvement leading to incredible strength. Weightlifters use his story to explain the Principle of Progressive Overload. Novice lifters are weak, so they begin by lifting light weights. Those weights stimulate muscle growth, allowing them to lift slightly heavier. Those heavier weights provoke more muscle growth, allowing them to lift heavier still.

Milo is a historical figure. He almost certainly existed. All the great historians of his time referenced him, including both Herodotus and Aristotle. He lived alongside figures like Pythagoras. However, these old stories are so heavily shrouded by the mists of time they’re nigh indistinguishable from legend.

Here is the Legend of Milo of Croton.

Read MoreAn Anecdote for Lowering Work Morale by Heinrich Boll

Anecdote for Lowering Work Morale (Anekdote zur Senkung der Arbeitsmoral) is a short story written by the Nobel Prize-winning German author Heinrich Boll in 1963. It’s a parable about the value of ambition, complacency, and capitalism. It serves as a critique of the modern work ethic.

Almost all of the stories on this site are retellings in my own words. This one isn’t. I’ve translated it from German into English but otherwise left it the same.

Read MoreThe Donkey and the Onager (Aesopic Fables)

There are two Aesopic fables about a donkey and an onager. The first fable was recorded by Syntipas in the 11th century. The second comes from the French scholar Émile Chambry in 1925. It appears they disagreed with one another about what the moral lesson ought to be, giving us twin fables with opposite endings. They’re best when told together, as I’ve done here.

As is tradition, these are retellings in my own words.

Fable 1: The Donkey, the Onager and the Lion

One evening, an onager (a wild donkey) came upon a donkey standing in a meadow. The onager admired the donkey’s condition, noting his bulging muscles and ample belly.

A little while later, the onager returned, hoping to learn the donkey’s secret. This time, he found the poor beast labouring under a heavy load with a man following along behind, harrying him with a club.

The onager sneered at the donkey, saying, “Lucky me! You rely on your oppressive master to feed you, whereas I roam free through the mountains, grazing where I please!”

But a lion lay in wait in a nearby thicket. It dared not leap upon the donkey, for it feared the master’s club. Instead, it pounced upon the onager.

Fable 1: The Onager, the Donkey and the Driver

Sometime later, another onager wandered down from the hills. She, too, noted how robust the donkey was. She watched with admiration as he carried his great load down the narrow road.

Then she saw the donkey’s master following along behind, brandishing his club. She didn’t like that. She returned to the hills, thinking it better to be free than to carry the burden of prosperity.

The Moral

The moral of the first fable is that the insubordinate are free from both obligation and protection. And so, perhaps it is better to live in service to a community, or in service to a master, both helping and being helped. This is the more ancient moral lesson, first recorded in the 11th century in the Byzantine Empire.

The Byzantine Empire used a system called pronoia, similar to the feudal system in Western Europe. The emperor gave out land to his lords, and those lords had to fight for the emperor. Those lords were also responsible for protecting the peasants who toiled away on their farmland, not so different from the master who harries but protects his donkey.

The moral of the second fable is that prosperity often comes at a great price. Perhaps it is better to be free, even if that means living more humbly. It’s a more modern moral lesson, from France in 1925.

Both fables stand in conflict with one another. That’s why they work so well together.

If you liked this fable, you may also enjoy The Mouse and the Lion.

The Little Mermaid (Classic Fairy Tale)

The Little Mermaid is a classic fairy tale written by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen in 1837. Some of these old fairy tales are fever dreams with illogical plots and incomprehensible character motivations. Andersen’s stories aren’t like that. They aged incredibly well.

This is the story of a young mermaid willing to give up her identity to gain a human soul and the love of a human prince. It does not end how the Disney version ends. It is a darker tale from a harsher time.

It was inspired by Danish folklore, mythology, and Andersen’s own personal experiences. In the 200 years since it was published, it has become widely recognized for its exploration of sacrifice, transformation, and unrequited love.

The original story was written in Danish. This is my own translation in my own words. It is a retelling of sorts, as any good translation is, but it stays true to the spirit of the original fairy tale.

The Original StoryThe Emperor’s New Clothes (Classic Fairy Tale)

The Emperor’s New Clothes is a story by Hans Christian Andersen published in 1837. It is a fairy tale with no magic or perhaps a fable with no animals. Either way, it is remarkable how many moral lessons Andersen was able to embed in such a short story.

As is tradition, this is a retelling in my own words.

The Fairy Tale

A long time ago, in a faraway kingdom, there lived an Emperor who was extremely fond of new clothes. He spent his time changing from one fabulous garment to another, parading around for his subjects to admire.

News of the Emperor’s vanity spread far and wide until it reached the ears of two cunning weavers. Seeing an opportunity, they journeyed to the kingdom, promising they could weave the most magnificent fabric imaginable. The unique quality of this material, they said, was that only the wise could see it.

The Emperor thought this was an excellent opportunity to discover which of his ministers and courtiers were unfit for their positions. He paid the weavers a hefty sum so they could begin their work at once.

After a while, the Emperor sent his most trusted advisors to see how the work was progressing. The weavers invited them to inspect the loom. They all praised the material, expressing admiration for its colours and patterns.

Word of the garment’s beauty quickly spread through the court, and soon the Emperor himself came to see the marvellous garment. He was shocked when he could not see the cloth himself, but he was afraid of appearing foolish, so he lavished praise upon the weavers and their work, expressing his eagerness to wear the finished garments.

On the day of the grand procession, the weavers carefully dressed the Emperor in his new clothes, complimenting his appearance and explaining the intricacies of the designs. The Emperor nodded along, unwilling to admit he couldn’t see any of these supposed wonders.

As the Emperor paraded down the streets, his subjects, who had heard of the cloth’s strange properties, praised the invisible finery, not wanting to appear unwise themselves.

Finally, a small child, too young to understand the pretense everyone was upholding, cried out, “But he hasn’t got anything on!” The child’s innocent words broke the spell, and whispers started spreading among the crowd.

The Emperor heard the murmuring and felt a chill of doubt, but he held his head high. He decided to continue the procession even more majestically. After all, the only thing more magnificent than an emperor’s garments is the Emperor himself.

The Moral

The moral of The Emperor’s New Clothes is that when we try to impress others, we lose sight of what’s actually worth caring about. It’s a common moral. Tolstoy wrote about it, too, using the same analogy:

A rich man goes to a threadmaker to spin some fine (thin) threads. The threadmaker spins the finest threads she can, but they feel too coarse to the rich man, so he asks for even finer ones. She cannot spin finer ones, so she shows the man nothing, explaining how the threads are so fine that they cannot even be seen. The rich man is delighted and pays her a hefty sum of gold.

The Emperor’s New Clothes goes deeper, with a variety of other morals embedded into it:

- Peer pressure can lead us down silly paths.

- The situation gets worse with every lie.

- Our pride blinds us to reality.

- The fear of judgment can silence the truth.

- The popular opinion can be wrong.

- Sometimes, the naive are best able to see the truth.

- We ought to face humiliation with dignity.

These fairy tales with moral lessons are very similar to Jewish and Muslim folktales. Or you might like The Spider King and His Astrologer or perhaps The Man Who Never Lied.

Hans Christian Andersen also wrote the original Little Mermaid fairy tale. And if you like those classic fairy tales, you might like Sleeping Beauty by Charles Perrault.

The Lion and the Mouse (Aesop’s Fables)

The Lion and the Mouse is one of Aesop’s most famous fables. This version comes from the medieval French monk Adémar de Chabannes. He was likely translating a much earlier version recorded by Phaedrus, a former Roman slave from the first century BCE.

The fable is usually used to preach kindness to the weak, but it goes a bit deeper than that, especially when considered in the context of other fables. I’ll explain that at the end.

As is tradition with fables, this is a retelling in my own words.

The Fable

A lion was taking a nap under the shade of a large tree when a mouse accidentally ran over his tail. The Lion woke with a start and pounced upon the pitiful mouse.

The tiny Mouse, quivering in terror, begged the lion for mercy. The lion was hungry, be he saw no honour in killing such a wretched little creature, so he forgave the mouse and let him go.

Sometime later, the lion fell into a hunter’s trap. The net was strong and the Lion was unable to break free. The mighty lion, trembling with fury, asked the hunters for mercy. The hunters were amused by the idea of setting such a ferocious creature free. They laughed and did not let him go.

The mouse heard the lion’s roar and rushed over and found the lion trapped. That night, he scurried quietly beneath the net and gnawed at the ropes with his sharp teeth, freeing the lion.

The lion leapt into the hunters’ camp, making a feast of them.

The Moral

The Lion and the Mouse has a few moral lessons you could pin to it. The first is that we should never harm the small or the weak. The second is that kindness is never wasted.

Aesop has another fable about animals helping each other escape hunters, giving us another moral: even simple creatures consider each other’s plights and come to one another’s aid. I’m not sure that happens very often, but so it was said.

These are optimistic fables. Kindness is repaid, cruelty is punished, and all is right in the world. It feels just and satisfying. You might even get the impression that all fables are this way. But many are far more cynical, such as The Snake, the Farmer, and the Heron and The Mongoose and the Farmer’s Wife.

In fact, Aesop has another fable about a mouse and a lion (first recorded by Babrius): The Mouse and the Lion’s Mane. In this other story, a mouse scurries over the lion’s mane, and the lion leaps up, all the hairs on his body standing on end, and devours the mouse. A fox sees this and laughs at the lion for being startled by a harmless mouse. The lion explains that he wasn’t worried that the mouse would hurt him, but he had to check the bold advances of the insolent creature, lest the other animals learn to treat him with disrespect.

The lion is a recurring character in these fables. I recommend reading some of the lesser-known ones, like The Monkey and the Lion’s Breath. Or, for a more modern fable, try The Fox, the Duck, and the Lion.

Thoughts? Questions? Drop a comment below.

The Owl & the Grasshopper (Aesop’s Fables)

The Owl & the Grasshopper is one of Aesop’s fables, written in the 5th century BCE. There have been many versions told since then. This is one of those retellings, in my own words.

A long time ago, in an ancient jungle, there was a wise old Owl. The Owl had a daily routine: she would sleep during the day and hunt during the night. One day, a Grasshopper moved into the tree where the Owl lived.

The Grasshopper had the annoying habit of singing all through the day, disturbing the owl’s precious sleep. The Owl asked the Grasshopper to sing softly, explaining her need for daytime rest, but the Grasshopper paid no heed and continued to sing.

After many sleepless days, the Owl was losing her mind. She could not bear the incessant singing any longer, so she invited the Grasshopper over for dinner, saying, “I have heard that you have a beautiful voice, and I would love to hear you sing under the moonlight.”

The Grasshopper was flattered by the compliment and agreed to put on a performance. However, when he arrived that night, the Owl gobbled him up.

The Moral: Flattery is not proof of admiration. Do not let it throw you off your guard.

The Two Horses (Leo Tolstoy Fable)

The Two Horses is a dark fable written by Leo Tolstoy in 1880. Tolstoy is famous for writing War & Peace and Anna Karenina, two of the most common methods of torture inflicted upon high school students, but he also wrote a book of fables to scare younger children. This is a retelling in my own words.

A long time ago, in a small village, there lived two packhorses named Lightning and Thunder. They both belonged to a diligent herder who relied on them to carry his furs to the market.

Lightning, the front horse, was quiet and hardworking. He constantly put forth his best effort, pulling his own weight and more. Thunder, the hind horse, was loud but lazy. He did as little work as he could get away with, and he often lagged behind. Observing this, the herder transferred the load from Thunder to Lightning so that they might move more quickly.

Thunder, relieved of his burden, trotted along leisurely. He laughed at Lightning, saying, “Work hard and sweat, Lightning! The more you strive, the more they’ll make you work.”

After a tiring day, they arrived at the tavern. The herder, noticing the disparity in effort between his two horses, contemplated, “Why should I feed two horses when only one does the work? It would be more sensible to feed Lightning well and do away with Thunder.”

And so it came to pass that Thunder found himself made into a fine fur cloak.

Moral: Those who make themselves redundant are no longer needed. Or, in different circumstances, they become free.

The Crane & the Crab (Buddhist Fable)

The Crane and the Crab (Baka Jataka) is an old Buddhist fable that has been told for thousands of years to warn about the dangers of deceit. It serves as a warning both ways, with the deceived and deceiver both suffering a grim fate.

A long time ago, in a desolate wasteland, a crane could find no food to eat. He took flight, journeying over the barren land, until he came upon the Old Jungle. There, nestled between the palms, he found a shimmering pond teeming with fish.

It was the peak of summer, and the pond was low on water, revealing the fish swimming just below the glassy surface. Unaware of the crane’s predatory nature, the fish took shelter under his shadow, blissfully ignorant of his hunger. They must not have known what he was.

The crane, readying himself to spear a fish with his beak, paused. A thought had struck him. If he feasted upon one fish, the rest would scatter in fear, and it would be much harder to catch the others.

Noticing that the crane had become lost in thought, one of the larger fish asked, “Why are you so troubled, noble lord?”

“I am thinking about you,” the crane replied, scheming up a cunning plan. “The water in this pool is low, the food is growing scarcer by the day, and from my higher vantage point, I can see the water evaporating in the summer heat. I was wondering to myself, how will you survive?”

“And what are we to do, my lord?” said the fish.

The crane, with his plan now fully formed, proposed, “I could transport you all to a larger pool, flourishing with all five kinds of lotuses. A sanctuary where you could thrive. However, the journey is long, and I can only carry one of you at a time. It will take many day bring you all.”

The large fish shared the crane’s story with the others, and they all grew eager to journey to the promised land. Every morning, a fish would swim into the crane’s beak, and the crane would take it to a deserted area and gobble it up. He did this for many moons until the day arrived when there were no fish left, only an irascible hermit crab.

Approaching the crab, the crane suggested, “Honorable crab, I have relocated all the fish to a vast pool, covered all over with lotuses. Come along. I will take you, too.”

The crab asked, “How do you plan to carry me?”

“In my beak,” the crane replied.

“Ah, but my shell is hard and slippery.

The crab, cautious by nature, proposed an alternative, “My shell is tough and slippery. If you carry me in your beak, I could fall. I had better hold onto your neck instead. I have an astonishingly strong grip.”

“Very well,” said the crane, bending over to let the crab grab on. But as the crane flew over the deserted area, the crab saw the skeletons of all the fish the crane had eaten.

The crab had prepared for this. “If I die, you will die with me,” he said. “I will sever you head from your body.” And with that, he tightened his grip on the crane’s neck.

Terrified, the crane had no choice but to continue onwards, a very long way, until he finally found a deep pool of fish shaded by every type of lotus. The crane set the crab down hurriedly in the water, eager to be rid of him. But instead of releasing the crane from his grip, the crab nipped his head clean off.

You know, there is another Eastern fable you might enjoy about a Mongoose and a Farmer’s Wife.

Sleeping Beauty (Classic Fairy Tale)

Sleeping Beauty, or Sleeping Beauty in the Wood (La Belle au Bois Dormant), is a dark fairy tale from long ago, originally written by Charles Perrault in 1697 in France. Since then, it’s been adapted many times, softened with every retelling. That is the fate of any good story. It changes as it ages.

This retelling is closer to the original. It’s not a direct translation. The language is a bit too archaic for that. I tried to modernize the language while keeping the twists and turns the same. I hope you like it.

Read More